The Four Enemies of Design System Speed

Why your design system is not making you move faster

TL;DR

The journey to achieve speed with a design system is blocked by a "four-headed hydra": Unrealistic Deadlines, Wrong Estimates, Skill Gaps, and Knowledge Gaps. These four heads are interconnected, with Knowledge Gaps, rooted in cultural misalignment, being the hardest one to tackle. To overcome those four issues slowing down speed, design leaders need to focus on aligning design system's goals and objectives with the company culture, recruit and grow skilled people with system thinking capabilities and ensure teams achieve good estimates and plan realistic deadlines.

It was one of those days where two external designers were hired for three months by a PM to build an order flow for the launch of a new product. Because I had seen this dynamic before I wasn’t surprised to notice the designers didn’t use the design system nor did they design the user journey consistently with our other flows even after they got their comps reviewed.

When the team lead showed the results to management the feedback was: “why does it look completely different from the rest?”. The two external designers were now gone, the deadline was approaching, one internal designer was asked to fix this mess and I was asked to help.

We looked at the user journeys together, isolated the components and patterns that could be used from our design system, mapped the information architecture to the components structure. We had other newly built order flows already on production that were working well for other products and 80% of the components needed were available in the design system. It was just a matter of thinking systematically inside our ecosystem of products.

In the end the designer went on solo to redesign the whole order flow in just two weeks and delivered responsive designs that were on brand and consistent with our design language used for other products.

Why wasn’t this done from the beginning? Why waste more than three months for something that could have been done in a few weeks?

During my sixteen year career I've witnessed the extreme speed inside a startup building a whole mobile app from scratch in just ten days as well as the reality of redesigns of existing products taking over a year to complete in the enterprise sector.

In my conversations with other design systems practitioners I keep hearing about how leadership desires quicker go to market and dislikes when deadlines need to be pushed back, again and again. There are numerous reasons for project delays. Typically leaders hear that developers haven't finished coding or that designers are still working on a UI or that someone needs to give approval.

Design systems sometimes end up becoming the scapegoat for such delays, accused of not delivering a component on time, not being flexible enough or not being able to move at the same pace of product teams in general. Through the years working as a product designer and later leading UX in a dedicated design system team I noticed how managers complain about teams not hitting deadlines but are not able to understand the reasons why that happens. If a project is moving slowly the solution is not always to bring more people onboard, leaders have to deeply understand what is going on if they want to address the root causes.

After thinking a lot on how design system are correlated to projects delivery speed I want to share my thoughts on the main Four Enemies of Design System Speed I see present in product development and how to address them: Unrealistic Deadlines, Wrong Estimates, Skill Gaps, Knowledge Gaps.

Think of those four as the heads of a hydra: connected, correlated and feeding each other.

Unrealistic Deadlines

The reason a team gets an unrealistic deadline can vary but usually someone in leadership decides on a date on the calendar or maybe there is a special day coming, think of things like Black Friday, Xmas, National Day etc. When a day is fixed without consideration and understanding of what needs to be done and how long it might take this scenario is often a recipe for disaster because teams will rush decisions in order to get something done quick on time.

By doing that teams often create design debt and tech debt which might end up causing a delay in the project...or worse, maybe this project gets delivered on time, but the debt accumulates and the repercussions are going to be felt during future projects, sometimes years down the line but few people realize this.

Design debt is the accumulation of inconsistent, non-reusable styles and conventions, which eventually becomes a great weight making maintenance an impossible task and slows product growth. Technical debt is the cumulative impact of engineering shortcuts and bad code implemented for expediency, resulting in complex systems that place strain on the product, causing work that used to take days to now take months. What leadership rarely sees is that this debt isn't just "messy code", it is a tax on future speed. Work that used to take days now takes months because the foundation has been eroded.

Design debt and tech debt can be caused by other factors (see Skill Gap and Knowledge Gap later) but one of the most common reasons is the rush to complete something quickly on time because of an unrealistic deadline. This causes a very unhealthy loop, if a deadline is unrealistic and teams don’t manage to hit it there’s a delay and because of that a perception that things are going too slow. If the team does manage to hit the deadline but along the way accumulated design and tech debt this will cause potential future slower pace and delays for teams. Worst of all, if a team manages to release something in X amount of time they will always be expected to do so, if not faster. It doesn’t matter the quality and the debt that was created for future updates and reworks, if the PM can show pretty screens to leaders during a presentation the issue of debt will never popup on their radar.

How unrealistic deadlines affect design systems

When unrealistic deadlines are placed upon teams there’s a potential trickle down effect to the design system team. This trickle down effect is sadly the reality of many immature companies where the design system team is seen as a delivery team. When this is the case, design debt and tech debt get embedded in the system itself if no governance process is there to prevent it.

Designers under time pressure will also be more likely to detach and hack components just to be faster, and who can blame them when that’s their incentive. Such deviations will later be sent to developers which will often end up asking the design system team how to build such a design. The engineers will then be told by the system team that a certain UI is not possible or doesn’t follow the design system guidelines. Now the time for developing the deviation will need to be added to the planning, adding delays. The developer will blame the designer for not using the system and the designer will blame the design system team for not being flexible enough. Welcome to the blame game.

How to avoid unrealistic deadlines

An unrealistic deadline is often a symptom of a deeper problem: a failure of initial prioritization and scoping. The recipe for disaster is not just that the deadline is fixed, but that no one was empowered or required to push back on the scope after the deadline was set. One could argue that the real problem in this scenario is misaligned incentives or fear of pushback, which allows the unrealistic deadline to be accepted in the first place. If a deadline is fixed, the scope must be variable. This is the classic "Iron Triangle" of project management.

The design system team should be present at the start of the project, not the end. Their role is to look at the mockups and say: "If you use the standard component, we can ship in two weeks. If you want this custom custom component, it will take six weeks. Which one fits your deadline?" This puts the trade-off back in the hands of the PM.

Sometimes, to hit a deadline, you must ignore the system. That is okay, provided it is a conscious choice. A mature design system culture allows for a "one-off" today with a ticket created to "systematize" it next quarter. Speed now, cleanup later but only if the cleanup is actually planned.

It is important for leadership to distinguish, on one hand, wrong estimates and on the other hand misaligned incentives or fear of pushback. Misaligned incentives and fear of pushback are knowledge gap issues of company culture while wrong estimates can often be due to skill gaps as we’ll discuss later. We will address wrong estimates in the next section.

Wrong Estimates

Correct estimates can only be achieved when breaking down the project in all its parts and talking to the people assigned to craft and assemble those parts together. This presupposes there is an understanding of what needs to be done and an understanding of how people actually need to do the work.

This is not a given, many managers or people in leadership positions have no idea of how digital products are built and are not able to fully understand the interdependencies between disciplines like design and development. This is exacerbated in companies working using old school waterfall, where designers send engineers a Figma link to build and where product managers are approving images on screen during a presentation. Because product design is a messy endeavour especially during discovery phases it is also a reason why agile development tried to replace waterfall by introducing new ways to tackle projects backlogs, timelines etc. Sadly true agile development is not the reality in all companies, even those who claim to work agile but that’s another discussion for another day.

People and teams that have been working together for a long time and have skilled people will become better and better with time at estimating projects. In his article “The Fast and Slow of Design” Mark Boulton mentions the importance of the people work inside a design system team:

The people in a system are seldom acknowledged as a component of a system. Instead, they are people who act on a system. I think this is a mistake. People take work. In most organisations, the people of a system represent continuity and sometimes the only thing stopping it from being rebuilt and redesigned from external HIPPO (Highest Paid Person’s Opinion) influence.

This continuity I would argue is what gets hurt in any team when reorganisations or layoffs happen and end up affecting the team ability to properly estimate work.

Like mentioned before, the most important thing is that there needs to be an understanding of what needs to be done and an understanding of how people actually need to do the work.

How wrong estimates affect design systems

Wrong estimates are often related to skill gaps and knowledge gaps which we will analyze in the next sections. Oftentimes product teams incorrectly estimate their tasks by mistakenly thinking that something can be done using the design system. For example, I've seen designers think that they can add paddings, edit colors, move inner elements of existing components without understanding how such things are built in code. When engineers notice such deviations during development it’s often too late and previous estimations might result wrong.

This has repercussions on the design system team which is often asked to help solve the issue but as a result certain requirements need a component modification or an additional component variant. Those things can’t always be done by the system team on short notice, nor they should sometimes because we don’t want to add design debt and tech debt to the design system itself.

This bad spiral has the repercussion that the product team realized they have to modify or build something they didn’t plan to because they assumed the design system already offered this possibility. This implicates delays which are often blamed on the developers (because the design was finished right?) or on the design system team for not being flexible enoch to make possible any visual wish designers had.

This is the time where friction between product teams and the design system team often happens. There is clear misalignment here, lack of incentives, skill gaps and knowledge gap all mixed together. Let’s look at how we can mitigate such things so that they don’t happen to the extent that they slow down project delivery substantially.

How to avoid wrong estimates

As for unrealistic deadlines it must be said that estimates are never precise, therefore we call them “estimates”. There is a big difference between good estimates and totally wrong estimates: good estimates mitigate the risk of having totally wrong deadlines.

Estimating how long something takes to conceptualise, design, develop etc. is very hard but it’s something people get better with experience, it’s a skill. It’s hard to be perfect at estimates and many methodologies involve adding time buffers of error. Such buffers can also be adjusted in future projects by measuring teams performance at delivering planned tasks on time.

As mentioned before, learning how to estimate tasks in teams gets easier with time when teams are stable, things like reorganisations or layoffs can have a very bad impact and reset this learning. We all know what it means to work well with the same group of people for many years and how that helps in estimating tasks.

For this reason companies hiring temporary contractors or agencies to quickly design something in order to reach a deadline often end up with the opposite result. What often ends up happening is that external resources build something quick, often without being shepherded by internal designers and engineers but only by PMs or POs, the deliverables are not fully thought through and once they are supposed to go in development (the design is finished right?) the concepts fall apart, the edge cases start eroding the assumed deadlines, the internal teams are asked to patch the work quickly, design and tech debt accumulates…again.

This dynamic also happens internally, when external resources are not involved. Sometimes internal teams are siloed and each team works as its own “company” with its own PM as a CEO. There is nothing wrong in having “silos” inside a big company, it’s normal and grouping people in more manageable subsets of employees makes sense most of the time. What companies need are bridges between those silos. Bridges are made of people who can foster communication and alignment across teams and disciplines. Those people need to also be culturally aligned and have the right incentives. If one PM is told their product should adhere to WCAG AA standards for accessibility but another PM has no idea what accessibility is and finds the underline of some text “not pretty” you have two silos with two leaders who are misaligned and will send their teams in different directions, making the bridging harder if not impossible.

Such misalignments are due to a knowledge gap with roots in the company culture. We will explore knowledge gaps in the last section of this article but first let’s dive into another potential contributor to wrong estimates, skill gaps.

Skill Gap

A skill gap is all about the “how” problem: the inability to execute a task effectively or within an acceptable timeframe, even when the person knows what to do. This is a deficiency in practical ability or proficiency.

A designer knows they should use a design system component but lacks the proficiency in Figma to use its advanced features correctly (e.g., auto layout, tokens usage, nested instances), resulting in them detaching and hacking the component. Or, an engineer has to constantly ask how to build a received design, indicating a lack of technical expertise in implementing the component correctly from the codebase.

One quote from this Brian Chesky’s interview reminds me of this point:

…you know the old saying: "A players hire A players, B players hire C players" I would like to amend it: B players hire lots of C players, not just a few, but a lot, because those are the kind of people that like building empires. If you can't capably do your job, you don't hire people better than you, and a person less capable of you can't do the job. So you need like, three incapable people, because one incapable person can't actually do all the work. Now three incapable people are just going in three different directions, creating all these meetings and all this administrative tax.

This old saying was something I remember being told by a mentor of mine years ago. At the time I didn’t quite grasp it but later I saw this playing out exactly like Chesky is saying. A lot of people end up managing teams, but they don’t have the skills to manage the job, the actual job. They end up building an empire of incapable people, hired by those who can’t do the job.

It’s a hard truth, but if you want speed you need high performing teams made of people with skills led by someone who understands the work and can manage the work. If you don’t, you risk ending up with people creating meetings and administrative tax and an overall slow process like Chesky says. If you want speed, you undeniably need high-performing teams. However, when it comes to design systems, we must look at skill gaps through a bidirectional lens.

How skill gaps affect design systems

Skill gaps affect design systems in a huge way, both inside the design system team and inside the product teams. If a design system team as a whole lacks the skills to build a design system successfully the result will be product teams slowed down by using a tool that doesn’t work as it should. On the other hand if product teams don’t have the skills necessary to understand and use a design system, both from designers and engineers, the product teams will create unnecessary deviations, will reinvent the wheel, will create their own product patterns just for the sake of taste without having data to support it.

There is a second, more subtle danger. If a design system requires every single user to be a top 1% expert in Figma or React just to ship a simple feature, the system itself might be contributing to the gap. If a designer needs to understand complex token logic just to change a button color, or if a developer needs to wrestle with rigid props to make a minor adjustment, the system stops being an accelerator and starts becoming a gatekeeper. In this scenario, the design system team might blame the product team for "lacking skills," while the product team blames the system for being "over-engineered."

A successful design system relies on the expertise of two groups: those who build it and those who utilize it.

How to avoid skill gaps

Continuous education is the best way to mitigate one’s skill gaps in their career. In the context of design systems they are nowadays, for most big organisations, the new way of building digital products but often it’s assumed by leadership that people “just know” how to build using a design system. The reality, when you actually talk to people working in the space, is very different. There are many senior designers out there who never used a token, don’t know how to swap a nested slot into a component, can’t read HTML in the inspect of their browser. On the engineering side not everyone is familiar with Web Components or React or how to code design system components properly.

There has been a surge in design system teams wanting to promote education of design systems inside the organisation. This can take the form of tutorial videos, interactive courses, keynotes, linting tools, interactive documentations all developed internally by the design system team to promote the system and educate their consumers. Companies must treat the design system as a piece of software that requires onboarding. Senior and Lead designers, who may have been working a certain way for twenty years, often struggle the most with modern, systematic tooling. If the company expects them to update their skills, it must provide the time and incentives to do so.

The second step is to lower the barrier of entry for the design system. The system team must constantly ask: "Is this component hard to use because the user lacks skill, or because we made it too complex?" Great systems allow people to produce great work by providing guardrails and intuitive defaults. If you find that everyone has a skill gap regarding a specific component, it’s not a people problem, it’s a product problem. The solution is to simplify the API, improve the documentation, or automate the decision making.

Finally, hire for "system thinking". When recruiting, look beyond pure visual craft or coding speed. Look for “system thinking", the ability to see how a single piece fits into the whole. A designer who understands the concept of reusability will close their technical skill gap in Figma much faster than a brilliant visual artist who rejects the idea of structure.

Knowledge Gaps

The knowledge gaps defines the “what” or “why” of the problem: the lack of necessary information, awareness, or understanding of a system, process, or best practice. The person could do the job, but they don't know what the job is or what tools are available.

A designer starts a new project without realizing the company has a design system, this is the lack of a mandate. A product manager doesn't know the governance process for requesting a new component: this is organizational isolation. Let’s focus on these two concepts.

The lack of mandate is when product teams simply don't use the design system at all. If 50% of the company is building custom one-offs because the system isn't mandated or culturally enforced, the system team's velocity promise is irrelevant.

When there is organizational isolation on the other hand the design system team is structurally isolated (seen as a service provider rather than a partner) and doesn't have a direct line to product leadership for prioritization, their work can often be deprioritized, which slows down the entire product organization.

Those two issues are often ones where leadership, from heads of departments to PMs, are completely oblivious in companies where there’s a lack of true leadership in design and engineering. I had countless encounters with PMs and POs that were dumfounded when they discovered their teams didn’t use the design system. Some of their teams were just using the brand colors and typography so they assumed all was good.

Skills gaps trickle down inside teams: when at leadership level nobody can manage the work because they lack the skills to understand what the work is, there are knowledge gaps forming inside the teams.

Leaders lacking the required skills would not dare introducing a mandate because for a mandate to be implemented one has to understand how it trickles down to the teams, who is responsible and accountable for what, which new processes need to be put in place and most importantly which incentives should be put in place given the overall strategy of the company.

People often hate the word “mandate” and prefer to use the word “incentive”. Is there a mandate to use a company logo provided by the brand team or are people incentivized to use the correct logo asset? People argue that whenever you wonder why people behave a certain way you should always look at their incentives...I totally agree. Mandates work when you want to force a certain type of behavior from people who are incentivized to behave differently. It’s not the best way to run things but I understand that in huge companies a mandate might be faster and more efficient because aligning incentives across thousands of people is not an easy task.

How knowledge gaps affect design systems

When the "why" is missing, adoption creates friction. Teams that don't understand the long-term value of the system (scalability, accessibility, maintenance speed) will only see the short-term cost (learning curve, rigid constraints). This creates a culture where the design system is viewed as a "tax" on their speed rather than an enabler of it.

So many companies say they want their teams to do “more with less”, that’s one of their strategies. When there is a lack of incentive followed by a lack of accountability for the people managing those teams you can’t expect people to be incentivized to close their knowledge gap when it comes to design systems.

As mentioned before, the knowledge gap is about the “what” and the “why”. What does it mean to do more with less? Why should we use a design system? The knowledge gap prevents teams, even those with the right skills, to fully improve their development speed using a design system. This has repercussions for the design system because it stifles or even prevents adoption. This is obviously terrible as design systems can only show their real potential when adoption is spread and maintained.

How to avoid knowledge gaps

This is where company culture plays an important role. We have seen the interconnections of different issues I named enemies of design system speed but the knowledge gap is where work has to be done strategically within the culture of the organization.

Aligning strategy and incentives and fostering the right culture for the right type of company is key to address knowledge gaps. There has been tons of great work from Ben Callahan on how to work on company culture and what are the interplays with design systems so if you’re interested in his work check out his company Sparkbox.

I personally attended Ben’s Converge 2025 workshop on design systems maturity assessment and it made me realize how the wrong cultural alignment has a devastating impact on speed at organisations. Such misalignments have deep consequences often not seen by leadership, this is probably the hardest head of the hydra to tackle because it requires leadership to be on board and to challenge the existing company culture as well as someone with the knowledge and experience to mediate such transition.

In one of his articles about design systems culture Ben Callahan notes the importance of understanding the culture of the organization and to align the design system culture to it to avoid clashes. He writes:

The easiest way to alleviate these clashes is to swim with the current. In other words, a subculture that is the same as its parent culture is going to have fewer obstacles than one that is in opposition to it.

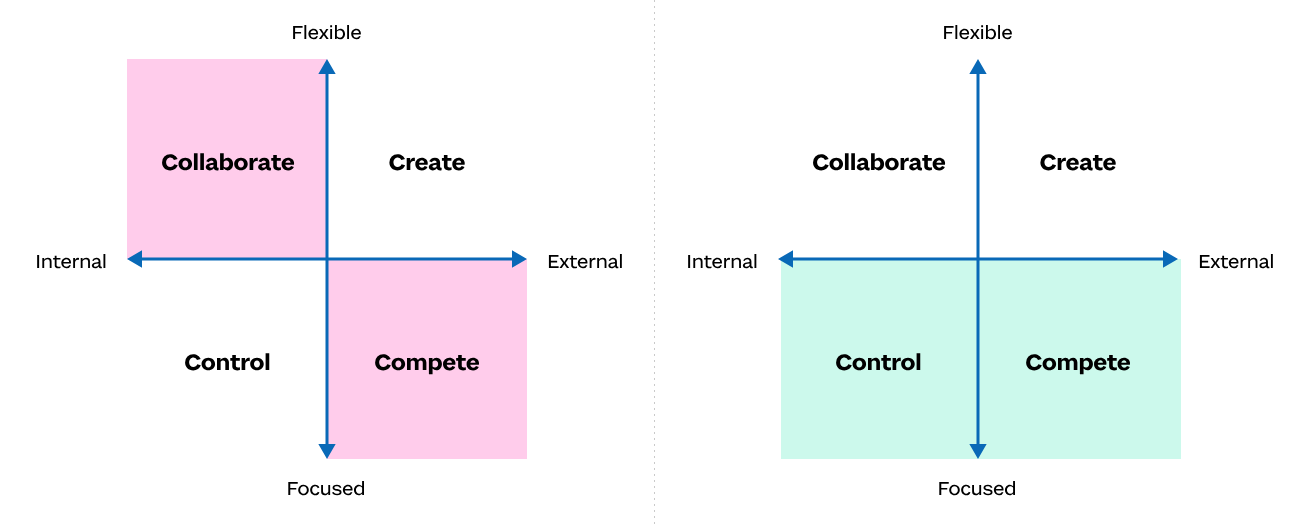

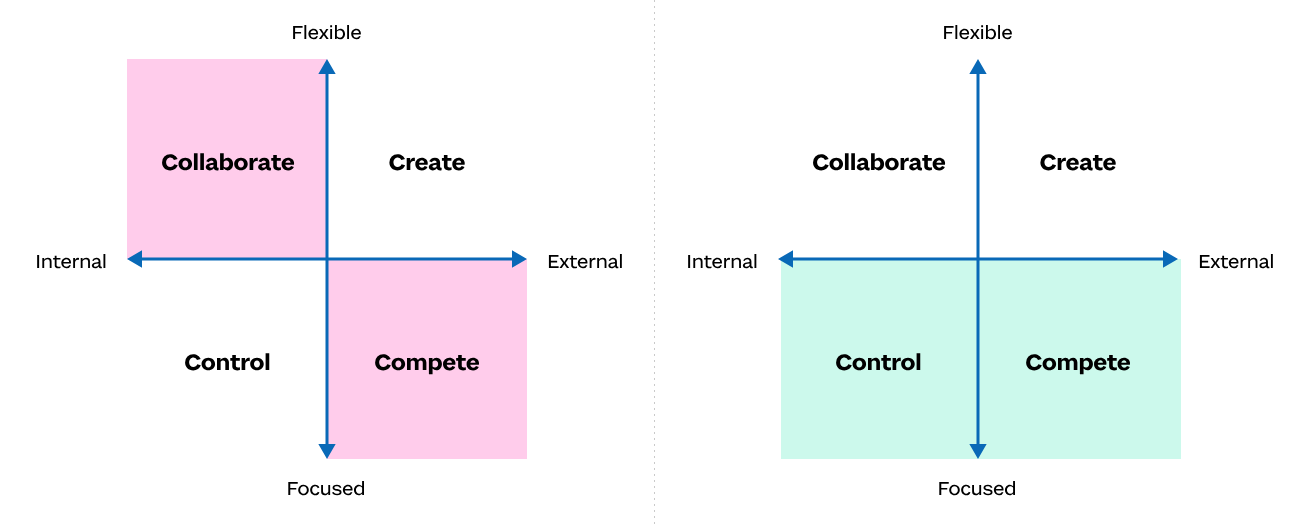

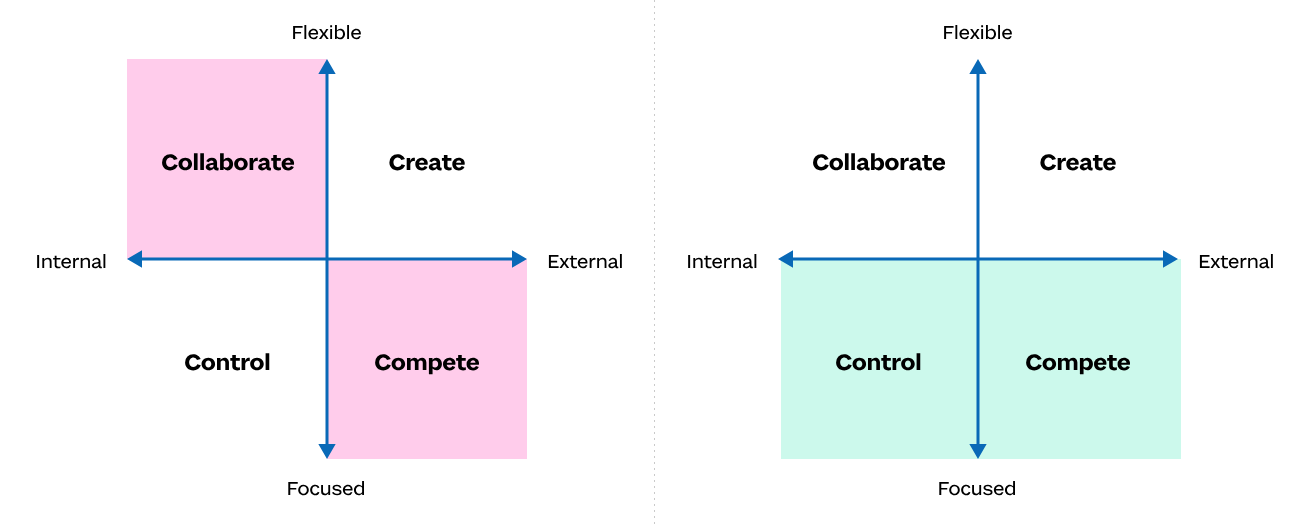

I think that in order to address the “what” and “why” of the knowledge gap companies have to understand their company culture and if a design system wants to enable speed it needs to be aligned with such culture. The Competing Values Framework below is one great example of how design system teams can analyze their organisation culture type and align to it rather than going against it.

From Sparkbox “Design System Culture” article

Work with leadership to change how success is measured. If a team ships a feature quickly but introduces twenty hard-coded colors and five inaccessible components, that shouldn't be celebrated as a "win". It should be flagged as "shipping with debt". When leadership starts valuing sustainable speed over reckless speed, the incentive to learn the design system appears naturally.

This is probably the hardest head of the hydra to defeat, it’s one that requires high levels of skills and self awareness from leadership, it requires leadership at the design level being able to set a design strategy on which the design system can align to.

Conclusion

The journey to achieving higher velocity with a design system is often obstructed by a "four-headed hydra" of issues: Unrealistic Deadlines, Wrong Estimates, Skill Gaps, and Knowledge Gaps. These heads are interconnected, with knowledge gaps, rooted in cultural misalignment that feeds skill gaps inside teams that end up with wrong estimates for projects with unrealistic deadlines.

We discussed how to face the four heads of the hydra and that it requires not just better execution, but a deeper understanding of why teams are slowing down. Each company has its own hydra with its own heads slowing down the company in some way. Each company faces a different monster and I hope I made you think about how that relates to your design system program currently at your organization.

In the example I gave in my introduction, the design of a new order flow for a new product, bridging the knowledge gap would have meant aligning the team’s PM incentives with the culture of the organization wanting to provide an omni-channel experience for their customers that looks consistent across products. This would have incentivized bringing the right skills onto the project, making sure people involved can leverage the company design system which is there to enable teams to consistently build digital experiences fast and with quality. By doing that, skilled team players would have been able to provide good estimates to their PMs and this would have led to a realistic deadline for the launch of the product.

To sum it up, if you want to move faster work on having an aligned culture between the organization and your design system, recruit and grow people with skills on how to leverage the new way of working a design system is and from that make sure your teams use their skills and experience working together to come up with good estimates that will be the base for more realistic deadlines. You can always move faster of course, but don’t let these four enemies of speed be the reason you struggle to do so.

The Four Enemies of Design System Speed

Why your design system is not making you move faster

TL;DR

The journey to achieve speed with a design system is blocked by a "four-headed hydra": Unrealistic Deadlines, Wrong Estimates, Skill Gaps, and Knowledge Gaps. These four heads are interconnected, with Knowledge Gaps, rooted in cultural misalignment, being the hardest one to tackle. To overcome those four issues slowing down speed, design leaders need to focus on aligning design system's goals and objectives with the company culture, recruit and grow skilled people with system thinking capabilities and ensure teams achieve good estimates and plan realistic deadlines.

It was one of those days where two external designers were hired for three months by a PM to build an order flow for the launch of a new product. Because I had seen this dynamic before I wasn’t surprised to notice the designers didn’t use the design system nor did they design the user journey consistently with our other flows even after they got their comps reviewed.

When the team lead showed the results to management the feedback was: “why does it look completely different from the rest?”. The two external designers were now gone, the deadline was approaching, one internal designer was asked to fix this mess and I was asked to help.

We looked at the user journeys together, isolated the components and patterns that could be used from our design system, mapped the information architecture to the components structure. We had other newly built order flows already on production that were working well for other products and 80% of the components needed were available in the design system. It was just a matter of thinking systematically inside our ecosystem of products.

In the end the designer went on solo to redesign the whole order flow in just two weeks and delivered responsive designs that were on brand and consistent with our design language used for other products.

Why wasn’t this done from the beginning? Why waste more than three months for something that could have been done in a few weeks?

During my sixteen year career I've witnessed the extreme speed inside a startup building a whole mobile app from scratch in just ten days as well as the reality of redesigns of existing products taking over a year to complete in the enterprise sector.

In my conversations with other design systems practitioners I keep hearing about how leadership desires quicker go to market and dislikes when deadlines need to be pushed back, again and again. There are numerous reasons for project delays. Typically leaders hear that developers haven't finished coding or that designers are still working on a UI or that someone needs to give approval.

Design systems sometimes end up becoming the scapegoat for such delays, accused of not delivering a component on time, not being flexible enough or not being able to move at the same pace of product teams in general. Through the years working as a product designer and later leading UX in a dedicated design system team I noticed how managers complain about teams not hitting deadlines but are not able to understand the reasons why that happens. If a project is moving slowly the solution is not always to bring more people onboard, leaders have to deeply understand what is going on if they want to address the root causes.

After thinking a lot on how design system are correlated to projects delivery speed I want to share my thoughts on the main Four Enemies of Design System Speed I see present in product development and how to address them: Unrealistic Deadlines, Wrong Estimates, Skill Gaps, Knowledge Gaps.

Think of those four as the heads of a hydra: connected, correlated and feeding each other.

Unrealistic Deadlines

The reason a team gets an unrealistic deadline can vary but usually someone in leadership decides on a date on the calendar or maybe there is a special day coming, think of things like Black Friday, Xmas, National Day etc. When a day is fixed without consideration and understanding of what needs to be done and how long it might take this scenario is often a recipe for disaster because teams will rush decisions in order to get something done quick on time.

By doing that teams often create design debt and tech debt which might end up causing a delay in the project...or worse, maybe this project gets delivered on time, but the debt accumulates and the repercussions are going to be felt during future projects, sometimes years down the line but few people realize this.

Design debt is the accumulation of inconsistent, non-reusable styles and conventions, which eventually becomes a great weight making maintenance an impossible task and slows product growth. Technical debt is the cumulative impact of engineering shortcuts and bad code implemented for expediency, resulting in complex systems that place strain on the product, causing work that used to take days to now take months. What leadership rarely sees is that this debt isn't just "messy code", it is a tax on future speed. Work that used to take days now takes months because the foundation has been eroded.

Design debt and tech debt can be caused by other factors (see Skill Gap and Knowledge Gap later) but one of the most common reasons is the rush to complete something quickly on time because of an unrealistic deadline. This causes a very unhealthy loop, if a deadline is unrealistic and teams don’t manage to hit it there’s a delay and because of that a perception that things are going too slow. If the team does manage to hit the deadline but along the way accumulated design and tech debt this will cause potential future slower pace and delays for teams. Worst of all, if a team manages to release something in X amount of time they will always be expected to do so, if not faster. It doesn’t matter the quality and the debt that was created for future updates and reworks, if the PM can show pretty screens to leaders during a presentation the issue of debt will never popup on their radar.

How unrealistic deadlines affect design systems

When unrealistic deadlines are placed upon teams there’s a potential trickle down effect to the design system team. This trickle down effect is sadly the reality of many immature companies where the design system team is seen as a delivery team. When this is the case, design debt and tech debt get embedded in the system itself if no governance process is there to prevent it.

Designers under time pressure will also be more likely to detach and hack components just to be faster, and who can blame them when that’s their incentive. Such deviations will later be sent to developers which will often end up asking the design system team how to build such a design. The engineers will then be told by the system team that a certain UI is not possible or doesn’t follow the design system guidelines. Now the time for developing the deviation will need to be added to the planning, adding delays. The developer will blame the designer for not using the system and the designer will blame the design system team for not being flexible enough. Welcome to the blame game.

How to avoid unrealistic deadlines

An unrealistic deadline is often a symptom of a deeper problem: a failure of initial prioritization and scoping. The recipe for disaster is not just that the deadline is fixed, but that no one was empowered or required to push back on the scope after the deadline was set. One could argue that the real problem in this scenario is misaligned incentives or fear of pushback, which allows the unrealistic deadline to be accepted in the first place. If a deadline is fixed, the scope must be variable. This is the classic "Iron Triangle" of project management.

The design system team should be present at the start of the project, not the end. Their role is to look at the mockups and say: "If you use the standard component, we can ship in two weeks. If you want this custom custom component, it will take six weeks. Which one fits your deadline?" This puts the trade-off back in the hands of the PM.

Sometimes, to hit a deadline, you must ignore the system. That is okay, provided it is a conscious choice. A mature design system culture allows for a "one-off" today with a ticket created to "systematize" it next quarter. Speed now, cleanup later but only if the cleanup is actually planned.

It is important for leadership to distinguish, on one hand, wrong estimates and on the other hand misaligned incentives or fear of pushback. Misaligned incentives and fear of pushback are knowledge gap issues of company culture while wrong estimates can often be due to skill gaps as we’ll discuss later. We will address wrong estimates in the next section.

Wrong Estimates

Correct estimates can only be achieved when breaking down the project in all its parts and talking to the people assigned to craft and assemble those parts together. This presupposes there is an understanding of what needs to be done and an understanding of how people actually need to do the work.

This is not a given, many managers or people in leadership positions have no idea of how digital products are built and are not able to fully understand the interdependencies between disciplines like design and development. This is exacerbated in companies working using old school waterfall, where designers send engineers a Figma link to build and where product managers are approving images on screen during a presentation. Because product design is a messy endeavour especially during discovery phases it is also a reason why agile development tried to replace waterfall by introducing new ways to tackle projects backlogs, timelines etc. Sadly true agile development is not the reality in all companies, even those who claim to work agile but that’s another discussion for another day.

People and teams that have been working together for a long time and have skilled people will become better and better with time at estimating projects. In his article “The Fast and Slow of Design” Mark Boulton mentions the importance of the people work inside a design system team:

The people in a system are seldom acknowledged as a component of a system. Instead, they are people who act on a system. I think this is a mistake. People take work. In most organisations, the people of a system represent continuity and sometimes the only thing stopping it from being rebuilt and redesigned from external HIPPO (Highest Paid Person’s Opinion) influence.

This continuity I would argue is what gets hurt in any team when reorganisations or layoffs happen and end up affecting the team ability to properly estimate work.

Like mentioned before, the most important thing is that there needs to be an understanding of what needs to be done and an understanding of how people actually need to do the work.

How wrong estimates affect design systems

Wrong estimates are often related to skill gaps and knowledge gaps which we will analyze in the next sections. Oftentimes product teams incorrectly estimate their tasks by mistakenly thinking that something can be done using the design system. For example, I've seen designers think that they can add paddings, edit colors, move inner elements of existing components without understanding how such things are built in code. When engineers notice such deviations during development it’s often too late and previous estimations might result wrong.

This has repercussions on the design system team which is often asked to help solve the issue but as a result certain requirements need a component modification or an additional component variant. Those things can’t always be done by the system team on short notice, nor they should sometimes because we don’t want to add design debt and tech debt to the design system itself.

This bad spiral has the repercussion that the product team realized they have to modify or build something they didn’t plan to because they assumed the design system already offered this possibility. This implicates delays which are often blamed on the developers (because the design was finished right?) or on the design system team for not being flexible enoch to make possible any visual wish designers had.

This is the time where friction between product teams and the design system team often happens. There is clear misalignment here, lack of incentives, skill gaps and knowledge gap all mixed together. Let’s look at how we can mitigate such things so that they don’t happen to the extent that they slow down project delivery substantially.

How to avoid wrong estimates

As for unrealistic deadlines it must be said that estimates are never precise, therefore we call them “estimates”. There is a big difference between good estimates and totally wrong estimates: good estimates mitigate the risk of having totally wrong deadlines.

Estimating how long something takes to conceptualise, design, develop etc. is very hard but it’s something people get better with experience, it’s a skill. It’s hard to be perfect at estimates and many methodologies involve adding time buffers of error. Such buffers can also be adjusted in future projects by measuring teams performance at delivering planned tasks on time.

As mentioned before, learning how to estimate tasks in teams gets easier with time when teams are stable, things like reorganisations or layoffs can have a very bad impact and reset this learning. We all know what it means to work well with the same group of people for many years and how that helps in estimating tasks.

For this reason companies hiring temporary contractors or agencies to quickly design something in order to reach a deadline often end up with the opposite result. What often ends up happening is that external resources build something quick, often without being shepherded by internal designers and engineers but only by PMs or POs, the deliverables are not fully thought through and once they are supposed to go in development (the design is finished right?) the concepts fall apart, the edge cases start eroding the assumed deadlines, the internal teams are asked to patch the work quickly, design and tech debt accumulates…again.

This dynamic also happens internally, when external resources are not involved. Sometimes internal teams are siloed and each team works as its own “company” with its own PM as a CEO. There is nothing wrong in having “silos” inside a big company, it’s normal and grouping people in more manageable subsets of employees makes sense most of the time. What companies need are bridges between those silos. Bridges are made of people who can foster communication and alignment across teams and disciplines. Those people need to also be culturally aligned and have the right incentives. If one PM is told their product should adhere to WCAG AA standards for accessibility but another PM has no idea what accessibility is and finds the underline of some text “not pretty” you have two silos with two leaders who are misaligned and will send their teams in different directions, making the bridging harder if not impossible.

Such misalignments are due to a knowledge gap with roots in the company culture. We will explore knowledge gaps in the last section of this article but first let’s dive into another potential contributor to wrong estimates, skill gaps.

Skill Gap

A skill gap is all about the “how” problem: the inability to execute a task effectively or within an acceptable timeframe, even when the person knows what to do. This is a deficiency in practical ability or proficiency.

A designer knows they should use a design system component but lacks the proficiency in Figma to use its advanced features correctly (e.g., auto layout, tokens usage, nested instances), resulting in them detaching and hacking the component. Or, an engineer has to constantly ask how to build a received design, indicating a lack of technical expertise in implementing the component correctly from the codebase.

One quote from this Brian Chesky’s interview reminds me of this point:

…you know the old saying: "A players hire A players, B players hire C players" I would like to amend it: B players hire lots of C players, not just a few, but a lot, because those are the kind of people that like building empires. If you can't capably do your job, you don't hire people better than you, and a person less capable of you can't do the job. So you need like, three incapable people, because one incapable person can't actually do all the work. Now three incapable people are just going in three different directions, creating all these meetings and all this administrative tax.

This old saying was something I remember being told by a mentor of mine years ago. At the time I didn’t quite grasp it but later I saw this playing out exactly like Chesky is saying. A lot of people end up managing teams, but they don’t have the skills to manage the job, the actual job. They end up building an empire of incapable people, hired by those who can’t do the job.

It’s a hard truth, but if you want speed you need high performing teams made of people with skills led by someone who understands the work and can manage the work. If you don’t, you risk ending up with people creating meetings and administrative tax and an overall slow process like Chesky says. If you want speed, you undeniably need high-performing teams. However, when it comes to design systems, we must look at skill gaps through a bidirectional lens.

How skill gaps affect design systems

Skill gaps affect design systems in a huge way, both inside the design system team and inside the product teams. If a design system team as a whole lacks the skills to build a design system successfully the result will be product teams slowed down by using a tool that doesn’t work as it should. On the other hand if product teams don’t have the skills necessary to understand and use a design system, both from designers and engineers, the product teams will create unnecessary deviations, will reinvent the wheel, will create their own product patterns just for the sake of taste without having data to support it.

There is a second, more subtle danger. If a design system requires every single user to be a top 1% expert in Figma or React just to ship a simple feature, the system itself might be contributing to the gap. If a designer needs to understand complex token logic just to change a button color, or if a developer needs to wrestle with rigid props to make a minor adjustment, the system stops being an accelerator and starts becoming a gatekeeper. In this scenario, the design system team might blame the product team for "lacking skills," while the product team blames the system for being "over-engineered."

A successful design system relies on the expertise of two groups: those who build it and those who utilize it.

How to avoid skill gaps

Continuous education is the best way to mitigate one’s skill gaps in their career. In the context of design systems they are nowadays, for most big organisations, the new way of building digital products but often it’s assumed by leadership that people “just know” how to build using a design system. The reality, when you actually talk to people working in the space, is very different. There are many senior designers out there who never used a token, don’t know how to swap a nested slot into a component, can’t read HTML in the inspect of their browser. On the engineering side not everyone is familiar with Web Components or React or how to code design system components properly.

There has been a surge in design system teams wanting to promote education of design systems inside the organisation. This can take the form of tutorial videos, interactive courses, keynotes, linting tools, interactive documentations all developed internally by the design system team to promote the system and educate their consumers. Companies must treat the design system as a piece of software that requires onboarding. Senior and Lead designers, who may have been working a certain way for twenty years, often struggle the most with modern, systematic tooling. If the company expects them to update their skills, it must provide the time and incentives to do so.

The second step is to lower the barrier of entry for the design system. The system team must constantly ask: "Is this component hard to use because the user lacks skill, or because we made it too complex?" Great systems allow people to produce great work by providing guardrails and intuitive defaults. If you find that everyone has a skill gap regarding a specific component, it’s not a people problem, it’s a product problem. The solution is to simplify the API, improve the documentation, or automate the decision making.

Finally, hire for "system thinking". When recruiting, look beyond pure visual craft or coding speed. Look for “system thinking", the ability to see how a single piece fits into the whole. A designer who understands the concept of reusability will close their technical skill gap in Figma much faster than a brilliant visual artist who rejects the idea of structure.

Knowledge Gaps

The knowledge gaps defines the “what” or “why” of the problem: the lack of necessary information, awareness, or understanding of a system, process, or best practice. The person could do the job, but they don't know what the job is or what tools are available.

A designer starts a new project without realizing the company has a design system, this is the lack of a mandate. A product manager doesn't know the governance process for requesting a new component: this is organizational isolation. Let’s focus on these two concepts.

The lack of mandate is when product teams simply don't use the design system at all. If 50% of the company is building custom one-offs because the system isn't mandated or culturally enforced, the system team's velocity promise is irrelevant.

When there is organizational isolation on the other hand the design system team is structurally isolated (seen as a service provider rather than a partner) and doesn't have a direct line to product leadership for prioritization, their work can often be deprioritized, which slows down the entire product organization.

Those two issues are often ones where leadership, from heads of departments to PMs, are completely oblivious in companies where there’s a lack of true leadership in design and engineering. I had countless encounters with PMs and POs that were dumfounded when they discovered their teams didn’t use the design system. Some of their teams were just using the brand colors and typography so they assumed all was good.

Skills gaps trickle down inside teams: when at leadership level nobody can manage the work because they lack the skills to understand what the work is, there are knowledge gaps forming inside the teams.

Leaders lacking the required skills would not dare introducing a mandate because for a mandate to be implemented one has to understand how it trickles down to the teams, who is responsible and accountable for what, which new processes need to be put in place and most importantly which incentives should be put in place given the overall strategy of the company.

People often hate the word “mandate” and prefer to use the word “incentive”. Is there a mandate to use a company logo provided by the brand team or are people incentivized to use the correct logo asset? People argue that whenever you wonder why people behave a certain way you should always look at their incentives...I totally agree. Mandates work when you want to force a certain type of behavior from people who are incentivized to behave differently. It’s not the best way to run things but I understand that in huge companies a mandate might be faster and more efficient because aligning incentives across thousands of people is not an easy task.

How knowledge gaps affect design systems

When the "why" is missing, adoption creates friction. Teams that don't understand the long-term value of the system (scalability, accessibility, maintenance speed) will only see the short-term cost (learning curve, rigid constraints). This creates a culture where the design system is viewed as a "tax" on their speed rather than an enabler of it.

So many companies say they want their teams to do “more with less”, that’s one of their strategies. When there is a lack of incentive followed by a lack of accountability for the people managing those teams you can’t expect people to be incentivized to close their knowledge gap when it comes to design systems.

As mentioned before, the knowledge gap is about the “what” and the “why”. What does it mean to do more with less? Why should we use a design system? The knowledge gap prevents teams, even those with the right skills, to fully improve their development speed using a design system. This has repercussions for the design system because it stifles or even prevents adoption. This is obviously terrible as design systems can only show their real potential when adoption is spread and maintained.

How to avoid knowledge gaps

This is where company culture plays an important role. We have seen the interconnections of different issues I named enemies of design system speed but the knowledge gap is where work has to be done strategically within the culture of the organization.

Aligning strategy and incentives and fostering the right culture for the right type of company is key to address knowledge gaps. There has been tons of great work from Ben Callahan on how to work on company culture and what are the interplays with design systems so if you’re interested in his work check out his company Sparkbox.

I personally attended Ben’s Converge 2025 workshop on design systems maturity assessment and it made me realize how the wrong cultural alignment has a devastating impact on speed at organisations. Such misalignments have deep consequences often not seen by leadership, this is probably the hardest head of the hydra to tackle because it requires leadership to be on board and to challenge the existing company culture as well as someone with the knowledge and experience to mediate such transition.

In one of his articles about design systems culture Ben Callahan notes the importance of understanding the culture of the organization and to align the design system culture to it to avoid clashes. He writes:

The easiest way to alleviate these clashes is to swim with the current. In other words, a subculture that is the same as its parent culture is going to have fewer obstacles than one that is in opposition to it.

I think that in order to address the “what” and “why” of the knowledge gap companies have to understand their company culture and if a design system wants to enable speed it needs to be aligned with such culture. The Competing Values Framework below is one great example of how design system teams can analyze their organisation culture type and align to it rather than going against it.

From Sparkbox “Design System Culture” article

Work with leadership to change how success is measured. If a team ships a feature quickly but introduces twenty hard-coded colors and five inaccessible components, that shouldn't be celebrated as a "win". It should be flagged as "shipping with debt". When leadership starts valuing sustainable speed over reckless speed, the incentive to learn the design system appears naturally.

This is probably the hardest head of the hydra to defeat, it’s one that requires high levels of skills and self awareness from leadership, it requires leadership at the design level being able to set a design strategy on which the design system can align to.

Conclusion

The journey to achieving higher velocity with a design system is often obstructed by a "four-headed hydra" of issues: Unrealistic Deadlines, Wrong Estimates, Skill Gaps, and Knowledge Gaps. These heads are interconnected, with knowledge gaps, rooted in cultural misalignment that feeds skill gaps inside teams that end up with wrong estimates for projects with unrealistic deadlines.

We discussed how to face the four heads of the hydra and that it requires not just better execution, but a deeper understanding of why teams are slowing down. Each company has its own hydra with its own heads slowing down the company in some way. Each company faces a different monster and I hope I made you think about how that relates to your design system program currently at your organization.

In the example I gave in my introduction, the design of a new order flow for a new product, bridging the knowledge gap would have meant aligning the team’s PM incentives with the culture of the organization wanting to provide an omni-channel experience for their customers that looks consistent across products. This would have incentivized bringing the right skills onto the project, making sure people involved can leverage the company design system which is there to enable teams to consistently build digital experiences fast and with quality. By doing that, skilled team players would have been able to provide good estimates to their PMs and this would have led to a realistic deadline for the launch of the product.

To sum it up, if you want to move faster work on having an aligned culture between the organization and your design system, recruit and grow people with skills on how to leverage the new way of working a design system is and from that make sure your teams use their skills and experience working together to come up with good estimates that will be the base for more realistic deadlines. You can always move faster of course, but don’t let these four enemies of speed be the reason you struggle to do so.

The Four Enemies of Design System Speed

Why your design system is not making you move faster

TL;DR

The journey to achieve speed with a design system is blocked by a "four-headed hydra": Unrealistic Deadlines, Wrong Estimates, Skill Gaps, and Knowledge Gaps. These four heads are interconnected, with Knowledge Gaps, rooted in cultural misalignment, being the hardest one to tackle. To overcome those four issues slowing down speed, design leaders need to focus on aligning design system's goals and objectives with the company culture, recruit and grow skilled people with system thinking capabilities and ensure teams achieve good estimates and plan realistic deadlines.

It was one of those days where two external designers were hired for three months by a PM to build an order flow for the launch of a new product. Because I had seen this dynamic before I wasn’t surprised to notice the designers didn’t use the design system nor did they design the user journey consistently with our other flows even after they got their comps reviewed.

When the team lead showed the results to management the feedback was: “why does it look completely different from the rest?”. The two external designers were now gone, the deadline was approaching, one internal designer was asked to fix this mess and I was asked to help.

We looked at the user journeys together, isolated the components and patterns that could be used from our design system, mapped the information architecture to the components structure. We had other newly built order flows already on production that were working well for other products and 80% of the components needed were available in the design system. It was just a matter of thinking systematically inside our ecosystem of products.

In the end the designer went on solo to redesign the whole order flow in just two weeks and delivered responsive designs that were on brand and consistent with our design language used for other products.

Why wasn’t this done from the beginning? Why waste more than three months for something that could have been done in a few weeks?

During my sixteen year career I've witnessed the extreme speed inside a startup building a whole mobile app from scratch in just ten days as well as the reality of redesigns of existing products taking over a year to complete in the enterprise sector.

In my conversations with other design systems practitioners I keep hearing about how leadership desires quicker go to market and dislikes when deadlines need to be pushed back, again and again. There are numerous reasons for project delays. Typically leaders hear that developers haven't finished coding or that designers are still working on a UI or that someone needs to give approval.

Design systems sometimes end up becoming the scapegoat for such delays, accused of not delivering a component on time, not being flexible enough or not being able to move at the same pace of product teams in general. Through the years working as a product designer and later leading UX in a dedicated design system team I noticed how managers complain about teams not hitting deadlines but are not able to understand the reasons why that happens. If a project is moving slowly the solution is not always to bring more people onboard, leaders have to deeply understand what is going on if they want to address the root causes.

After thinking a lot on how design system are correlated to projects delivery speed I want to share my thoughts on the main Four Enemies of Design System Speed I see present in product development and how to address them: Unrealistic Deadlines, Wrong Estimates, Skill Gaps, Knowledge Gaps.

Think of those four as the heads of a hydra: connected, correlated and feeding each other.

Unrealistic Deadlines

The reason a team gets an unrealistic deadline can vary but usually someone in leadership decides on a date on the calendar or maybe there is a special day coming, think of things like Black Friday, Xmas, National Day etc. When a day is fixed without consideration and understanding of what needs to be done and how long it might take this scenario is often a recipe for disaster because teams will rush decisions in order to get something done quick on time.

By doing that teams often create design debt and tech debt which might end up causing a delay in the project...or worse, maybe this project gets delivered on time, but the debt accumulates and the repercussions are going to be felt during future projects, sometimes years down the line but few people realize this.

Design debt is the accumulation of inconsistent, non-reusable styles and conventions, which eventually becomes a great weight making maintenance an impossible task and slows product growth. Technical debt is the cumulative impact of engineering shortcuts and bad code implemented for expediency, resulting in complex systems that place strain on the product, causing work that used to take days to now take months. What leadership rarely sees is that this debt isn't just "messy code", it is a tax on future speed. Work that used to take days now takes months because the foundation has been eroded.

Design debt and tech debt can be caused by other factors (see Skill Gap and Knowledge Gap later) but one of the most common reasons is the rush to complete something quickly on time because of an unrealistic deadline. This causes a very unhealthy loop, if a deadline is unrealistic and teams don’t manage to hit it there’s a delay and because of that a perception that things are going too slow. If the team does manage to hit the deadline but along the way accumulated design and tech debt this will cause potential future slower pace and delays for teams. Worst of all, if a team manages to release something in X amount of time they will always be expected to do so, if not faster. It doesn’t matter the quality and the debt that was created for future updates and reworks, if the PM can show pretty screens to leaders during a presentation the issue of debt will never popup on their radar.

How unrealistic deadlines affect design systems

When unrealistic deadlines are placed upon teams there’s a potential trickle down effect to the design system team. This trickle down effect is sadly the reality of many immature companies where the design system team is seen as a delivery team. When this is the case, design debt and tech debt get embedded in the system itself if no governance process is there to prevent it.

Designers under time pressure will also be more likely to detach and hack components just to be faster, and who can blame them when that’s their incentive. Such deviations will later be sent to developers which will often end up asking the design system team how to build such a design. The engineers will then be told by the system team that a certain UI is not possible or doesn’t follow the design system guidelines. Now the time for developing the deviation will need to be added to the planning, adding delays. The developer will blame the designer for not using the system and the designer will blame the design system team for not being flexible enough. Welcome to the blame game.

How to avoid unrealistic deadlines

An unrealistic deadline is often a symptom of a deeper problem: a failure of initial prioritization and scoping. The recipe for disaster is not just that the deadline is fixed, but that no one was empowered or required to push back on the scope after the deadline was set. One could argue that the real problem in this scenario is misaligned incentives or fear of pushback, which allows the unrealistic deadline to be accepted in the first place. If a deadline is fixed, the scope must be variable. This is the classic "Iron Triangle" of project management.

The design system team should be present at the start of the project, not the end. Their role is to look at the mockups and say: "If you use the standard component, we can ship in two weeks. If you want this custom custom component, it will take six weeks. Which one fits your deadline?" This puts the trade-off back in the hands of the PM.

Sometimes, to hit a deadline, you must ignore the system. That is okay, provided it is a conscious choice. A mature design system culture allows for a "one-off" today with a ticket created to "systematize" it next quarter. Speed now, cleanup later but only if the cleanup is actually planned.

It is important for leadership to distinguish, on one hand, wrong estimates and on the other hand misaligned incentives or fear of pushback. Misaligned incentives and fear of pushback are knowledge gap issues of company culture while wrong estimates can often be due to skill gaps as we’ll discuss later. We will address wrong estimates in the next section.

Wrong Estimates

Correct estimates can only be achieved when breaking down the project in all its parts and talking to the people assigned to craft and assemble those parts together. This presupposes there is an understanding of what needs to be done and an understanding of how people actually need to do the work.

This is not a given, many managers or people in leadership positions have no idea of how digital products are built and are not able to fully understand the interdependencies between disciplines like design and development. This is exacerbated in companies working using old school waterfall, where designers send engineers a Figma link to build and where product managers are approving images on screen during a presentation. Because product design is a messy endeavour especially during discovery phases it is also a reason why agile development tried to replace waterfall by introducing new ways to tackle projects backlogs, timelines etc. Sadly true agile development is not the reality in all companies, even those who claim to work agile but that’s another discussion for another day.

People and teams that have been working together for a long time and have skilled people will become better and better with time at estimating projects. In his article “The Fast and Slow of Design” Mark Boulton mentions the importance of the people work inside a design system team:

The people in a system are seldom acknowledged as a component of a system. Instead, they are people who act on a system. I think this is a mistake. People take work. In most organisations, the people of a system represent continuity and sometimes the only thing stopping it from being rebuilt and redesigned from external HIPPO (Highest Paid Person’s Opinion) influence.

This continuity I would argue is what gets hurt in any team when reorganisations or layoffs happen and end up affecting the team ability to properly estimate work.

Like mentioned before, the most important thing is that there needs to be an understanding of what needs to be done and an understanding of how people actually need to do the work.

How wrong estimates affect design systems

Wrong estimates are often related to skill gaps and knowledge gaps which we will analyze in the next sections. Oftentimes product teams incorrectly estimate their tasks by mistakenly thinking that something can be done using the design system. For example, I've seen designers think that they can add paddings, edit colors, move inner elements of existing components without understanding how such things are built in code. When engineers notice such deviations during development it’s often too late and previous estimations might result wrong.

This has repercussions on the design system team which is often asked to help solve the issue but as a result certain requirements need a component modification or an additional component variant. Those things can’t always be done by the system team on short notice, nor they should sometimes because we don’t want to add design debt and tech debt to the design system itself.

This bad spiral has the repercussion that the product team realized they have to modify or build something they didn’t plan to because they assumed the design system already offered this possibility. This implicates delays which are often blamed on the developers (because the design was finished right?) or on the design system team for not being flexible enoch to make possible any visual wish designers had.

This is the time where friction between product teams and the design system team often happens. There is clear misalignment here, lack of incentives, skill gaps and knowledge gap all mixed together. Let’s look at how we can mitigate such things so that they don’t happen to the extent that they slow down project delivery substantially.

How to avoid wrong estimates

As for unrealistic deadlines it must be said that estimates are never precise, therefore we call them “estimates”. There is a big difference between good estimates and totally wrong estimates: good estimates mitigate the risk of having totally wrong deadlines.

Estimating how long something takes to conceptualise, design, develop etc. is very hard but it’s something people get better with experience, it’s a skill. It’s hard to be perfect at estimates and many methodologies involve adding time buffers of error. Such buffers can also be adjusted in future projects by measuring teams performance at delivering planned tasks on time.

As mentioned before, learning how to estimate tasks in teams gets easier with time when teams are stable, things like reorganisations or layoffs can have a very bad impact and reset this learning. We all know what it means to work well with the same group of people for many years and how that helps in estimating tasks.

For this reason companies hiring temporary contractors or agencies to quickly design something in order to reach a deadline often end up with the opposite result. What often ends up happening is that external resources build something quick, often without being shepherded by internal designers and engineers but only by PMs or POs, the deliverables are not fully thought through and once they are supposed to go in development (the design is finished right?) the concepts fall apart, the edge cases start eroding the assumed deadlines, the internal teams are asked to patch the work quickly, design and tech debt accumulates…again.

This dynamic also happens internally, when external resources are not involved. Sometimes internal teams are siloed and each team works as its own “company” with its own PM as a CEO. There is nothing wrong in having “silos” inside a big company, it’s normal and grouping people in more manageable subsets of employees makes sense most of the time. What companies need are bridges between those silos. Bridges are made of people who can foster communication and alignment across teams and disciplines. Those people need to also be culturally aligned and have the right incentives. If one PM is told their product should adhere to WCAG AA standards for accessibility but another PM has no idea what accessibility is and finds the underline of some text “not pretty” you have two silos with two leaders who are misaligned and will send their teams in different directions, making the bridging harder if not impossible.

Such misalignments are due to a knowledge gap with roots in the company culture. We will explore knowledge gaps in the last section of this article but first let’s dive into another potential contributor to wrong estimates, skill gaps.

Skill Gap

A skill gap is all about the “how” problem: the inability to execute a task effectively or within an acceptable timeframe, even when the person knows what to do. This is a deficiency in practical ability or proficiency.

A designer knows they should use a design system component but lacks the proficiency in Figma to use its advanced features correctly (e.g., auto layout, tokens usage, nested instances), resulting in them detaching and hacking the component. Or, an engineer has to constantly ask how to build a received design, indicating a lack of technical expertise in implementing the component correctly from the codebase.

One quote from this Brian Chesky’s interview reminds me of this point:

…you know the old saying: "A players hire A players, B players hire C players" I would like to amend it: B players hire lots of C players, not just a few, but a lot, because those are the kind of people that like building empires. If you can't capably do your job, you don't hire people better than you, and a person less capable of you can't do the job. So you need like, three incapable people, because one incapable person can't actually do all the work. Now three incapable people are just going in three different directions, creating all these meetings and all this administrative tax.

This old saying was something I remember being told by a mentor of mine years ago. At the time I didn’t quite grasp it but later I saw this playing out exactly like Chesky is saying. A lot of people end up managing teams, but they don’t have the skills to manage the job, the actual job. They end up building an empire of incapable people, hired by those who can’t do the job.

It’s a hard truth, but if you want speed you need high performing teams made of people with skills led by someone who understands the work and can manage the work. If you don’t, you risk ending up with people creating meetings and administrative tax and an overall slow process like Chesky says. If you want speed, you undeniably need high-performing teams. However, when it comes to design systems, we must look at skill gaps through a bidirectional lens.

How skill gaps affect design systems

Skill gaps affect design systems in a huge way, both inside the design system team and inside the product teams. If a design system team as a whole lacks the skills to build a design system successfully the result will be product teams slowed down by using a tool that doesn’t work as it should. On the other hand if product teams don’t have the skills necessary to understand and use a design system, both from designers and engineers, the product teams will create unnecessary deviations, will reinvent the wheel, will create their own product patterns just for the sake of taste without having data to support it.

There is a second, more subtle danger. If a design system requires every single user to be a top 1% expert in Figma or React just to ship a simple feature, the system itself might be contributing to the gap. If a designer needs to understand complex token logic just to change a button color, or if a developer needs to wrestle with rigid props to make a minor adjustment, the system stops being an accelerator and starts becoming a gatekeeper. In this scenario, the design system team might blame the product team for "lacking skills," while the product team blames the system for being "over-engineered."

A successful design system relies on the expertise of two groups: those who build it and those who utilize it.

How to avoid skill gaps